TL;DR

- NFS is a multiple reader/multiple writer protocol to allow sharing a local filesystem over a network. It’s not a distributed filesystem as it’s layered on top of a normal local filesystem.

- It specifies certain guarantees regarding consistency in its specification to make this sharing safe. Those guarantees can result in unexpectedly low performance in pathological workloads.

- In order to deliver high performance even in those workloads while maintaining these guarantees, care must be taken that the NFS server is able to commit data (and required metadata) to non-volatile storage with the lowest possible latency.

Background

Sometimes it is very simple questions that lead you deep into the abyss of technical interdependencies. This text is about such a question. I was confronted with the problem in 2014. This text is a revised version of a text I wrote some time later, in 2017. In this revised version you will find an update about the situation with NFS v4.1.

Back then, the problem was not figuring out why the problem presented itself the way the customer described it. That was already very obvious at the start. The challenge was to explain how this phenomenon arises.

Before this situation, i saw the problem a couple of times.Since then, I have seen the problem a few more times. The text whose revised version you now have before you was already, in 2017, the result of repeated questions.

At its core, it is about the statement: “I used to have a SAN and my tar -x ran very fast. Now I have a ZFS Storage Appliance, use NFS, and the times for tar -x are terrible. 61 minutes.” I wrote the article back then so that in future cases I could simply and politely refer to this text. I recreated all packet traces on my own system.

The usefulness of this article goes far beyond Solaris or ZFSSA. It concerns NFS itself, as it is a consequence of design decisions inherent to NFS. Therefore, this text may also be of interest to users of other operating systems.

The fundamental misunderstanding arises because one might believe that NFS is simple—just a simple local filesystem shared over the network. But it is not simple.

A filesystem that provides network-wide “multiple reader/multiple writer” access to a local filesystem while taking locking and cache coherence into account cannot be simple—at least not as simple as a filesystem that only accesses a disk locally and has complete sole control over the data.

Back to that customer: I thought back then, when I first heard about this problem, “NFS and tar.” That is a known and understood problem. I think I first encountered this problem at the beginning of this millennium, when I started at Sun, and I knew what to look for.

I looked into the ZFSSA hardware configuration. And there was already the trigger: there wasn’t a single write-accelerating SSD in the configuration. At that point I could have said: “Dear customer, buy write accelerators and it will work. Best regards, Jörg Möllenkamp.” But before a customer spends an amount of money that is not 0 euros, they quite rightly want a precise explanation. And that explanation is what follows.

Even if a customer says they can accept a certain runtime behavior, they usually still want to know why it is the way it is, in order to check for themselves whether this challenge might hit them somewhere else as well.

Why did the customer need a write-accelerating SSD?

Problem

To describe the problem once again precisely: In this case, tar is used as a backup and replication mechanism. For this, the data directory of a program is packed with tar. If the dataset is to be replicated to a second server or the original server is to be restored after a failure, then this tarball is packaged and unpacked elsewhere.

The tarball contains a total of 290,000 files. Before the change, the storage was local and the tarball could be unpacked in a very short time. It was around one or two minutes. Then the customer changed the procedure such that unpacking was done into an NFS share. An unpack operation that previously took a short time then took 61 minutes.

Analysis

First you have to know what kind of load tar actually is—and why tar is such a load. To unpack a tarball, the corresponding program goes through the file sequentially. That is necessary because a tarball has no central directory that indicates the position of a packed file. So you can’t simply look at a spot in the file, find out where the first 32 files start and how long they are, and then unpack 32 files in one go. You have to read the tarball completely to find out where the individual files in the tarball are located. And then you might as well write the files out immediately.

There is a good reason why tar is built this way. tar stands for “tape archive.” Tapes are notoriously bad for non-sequential access. It makes no sense to restore multiple files simultaneously from a tape when the medium itself moves forward linearly and everything else would simply lead to tape- and drive-damaging shoeshining (imagine the cloth at shoe shining being moved back and forth over the shoe, and then imagine that with a read/write head and the tape).

So tar is, by design, a stubbornly sequential workload without any parallelization. As a side note: It is interesting that a compression program—one that can only pack a single file into a single compressed file—became widely established, and that we use a program for tape backups as a workaround for this problem. Though: it fits the Unix mindset. You pipe programs together, each with a single simple purpose, to solve bigger problems.

At this point it is interesting to relate the factors number of files and time. 290,000 files in 61 minutes means 12.62 milliseconds per file. That is not so bad for hard disks at first glance. Even with the fastest rotating disks these aren’t more than maybe two to three disk IOPs. Sometimes things simply take a long time because many very short steps are executed sequentially in large numbers. 290,000 times something very short is still a long time.

But why was it so much faster on local storage? Why does it need 12 milliseconds per file? There is obviously a large difference between 1 or 2 minutes on one hand and 61 minutes on the other.

The answer is simple: For all the complexity inherent in a local filesystem, it is comparatively simple. You have only one server writing into this filesystem. The system is the only source of truth. You can use many techniques: you can cache many things and write them to disk later, because only this system could have caused a change. A change cannot be sitting in another system’s cache. You can always reconcile the local cache and the on-disk state into a correct state. More important: You can have a lot of asynchronous file operations.

In a network filesystem this is completely different. Another node may have changed the information and your cache contents are “stale” with respect to this file. Another node does not have your cache to provide the whole truth about the filesystem state. If I create a directory on one server, it must be visible on another server. Therefore many things work differently with NFS—and you must keep that in mind when approaching an NFS performance problem.

I will show examples between two Solaris 11.4 systems. The communications may look slightly different with other client or server implementations.

This happens when you unpack a tarball locally:

0.0165 0.0002 openat64(4, "testfile1", O_RDWR|O_CREAT|O_TRUNC, 0100600) = 5

0.0169 0.0003 fstat64(5, 0xFD4E2AA0) = 0

0.0170 0.0001 write(5, "000000000000".., 1024) = 1024

0.0174 0.0000 close(5) = 0

I would like to draw your attention here to the flags when opening: O_RDWR|O_CREAT|O_TRUNC. This open() call does not specify any special behavior regarding synchronous I/O. There is no O_SYNC. And of course this will be fast. These writes will not reach disk as long as the ZFS transaction group has not been written to non-volatile storage (greatly simplified; reality is a bit more complicated).

But local filesystems are not our problem here. If you unpack the same file into a directory that is provided via NFS, you will see the following output in a packet sniffer:

1 0.000000 0.000000 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 194 V3 LOOKUP Call, DH: 0xad487762/singlefile

2 0.000178 0.000178 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 186 V3 LOOKUP Reply (Call In 1) Error: NFS3ERR_NOENT

3 0.000260 0.000438 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 178 V3 GETATTR Call, FH: 0xad487762

4 0.000052 0.000490 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 182 V3 GETATTR Reply (Call In 3) Directory mode: 0777 uid: 0 gid: 0

5 0.000242 0.000732 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 226 V3 MKDIR Call, DH: 0xad487762/singlefile

6 0.003430 0.004162 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 342 V3 MKDIR Reply (Call In 5)

7 0.000303 0.004465 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 178 V3 GETATTR Call, FH: 0xad487762

8 0.000053 0.004518 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 182 V3 GETATTR Reply (Call In 7) Directory mode: 0777 uid: 0 gid: 0

9 0.000273 0.004791 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 182 V3 ACCESS Call, FH: 0x44856022, [Check: RD LU MD XT DL]

10 0.000070 0.004861 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 190 V3 ACCESS Reply (Call In 9), [Allowed: RD LU MD XT DL]

11 0.000215 0.005076 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 178 V3 GETATTR Call, FH: 0x44856022

12 0.000076 0.005152 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 182 V3 GETATTR Reply (Call In 11) Directory mode: 0755 uid: 100 gid: 10

13 0.000175 0.005327 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 194 V3 LOOKUP Call, DH: 0x44856022/testfile1

14 0.000044 0.005371 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 186 V3 LOOKUP Reply (Call In 13) Error: NFS3ERR_NOENT

15 0.000188 0.005559 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 178 V3 GETATTR Call, FH: 0x44856022

16 0.000035 0.005594 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 182 V3 GETATTR Reply (Call In 15) Directory mode: 0755 uid: 100 gid: 10

17 0.000179 0.005773 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 178 V3 GETATTR Call, FH: 0x44856022

18 0.000033 0.005806 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 182 V3 GETATTR Reply (Call In 17) Directory mode: 0755 uid: 100 gid: 10

19 0.000166 0.005972 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 178 V3 GETATTR Call, FH: 0x44856022

20 0.000030 0.006002 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 182 V3 GETATTR Reply (Call In 19) Directory mode: 0755 uid: 100 gid: 10

21 0.000191 0.006193 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFSACL 182 V3 GETACL Call

22 0.000034 0.006227 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFSACL 206 V3 GETACL Reply (Call In 21)

23 0.000203 0.006430 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 194 V3 LOOKUP Call, DH: 0x44856022/testfile1

24 0.000033 0.006463 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 186 V3 LOOKUP Reply (Call In 23) Error: NFS3ERR_NOENT

25 0.000155 0.006618 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 238 V3 CREATE Call, DH: 0x44856022/testfile1 Mode: GUARDED

26 0.001257 0.007875 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 342 V3 CREATE Reply (Call In 25)

27 0.000189 0.008064 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 178 V3 GETATTR Call, FH: 0xd98a8154

28 0.000032 0.008096 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 182 V3 GETATTR Reply (Call In 27) Regular File mode: 0600 uid: 100 gid: 10

29 0.000237 0.008333 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 1222 V3 WRITE Call, FH: 0xd98a8154 Offset: 0 Len: 1024 FILE_SYNC

30 0.001254 0.009587 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 230 V3 WRITE Reply (Call In 29) Len: 1024 FILE_SYNC

31 0.000202 0.009789 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 178 V3 GETATTR Call, FH: 0xd98a8154

32 0.000037 0.009826 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 182 V3 GETATTR Reply (Call In 31) Regular File mode: 0600 uid: 100 gid: 10

33 0.000172 0.009998 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 222 V3 SETATTR Call, FH: 0xd98a8154

34 0.001084 0.011082 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 214 V3 SETATTR Reply (Call In 33)

35 0.000255 0.011337 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 222 V3 SETATTR Call, FH: 0x44856022

36 0.000997 0.012334 10.0.2.10 -> 10.0.2.11 NFS 214 V3 SETATTR Reply (Call In 35)

This is a NFSv3 mount without additional options. So the default NFS options between two Solaris systems apply.

You can see that quite a lot is going on. One could say the performance difference between a local tar and tar into an NFS filesystem is the network. And indeed, network latency matters when each file triggers many RPCs. Newer versions of the NFS protocol address this more explicitly: NFSv4 can reduce round trips via COMPOUND operations (batching multiple operations into a single RPC) and via delegations, which can allow clients to cache file state more aggressively in some scenarios.

That’s only half the story. It does not explain the 12 ms per file. Another reason is the way NFS transforms the workload.

In RFC 1813 there is a very important passage: “Data-modifying operations in the NFS version 3 protocol are synchronous. When a procedure returns to the client, the client can assume that the operation has completed and any data associated with the request is now on stable storage.”

It continues: “The following data modifying procedures are synchronous: WRITE (with stable flag set to FILE_SYNC), CREATE,MKDIR, SYMLINK, MKNOD, REMOVE, RMDIR, RENAME, LINK, and COMMIT.”

In the Solaris server implementation I examined, SETATTR handling appears to trigger synchronous persistence of the relevant metadata, which adds another latency-bound step per file.

If you look at the tcpdump above, you see a significant number of those NFS operations. And now imagine that for a tar file with 290,000 files.

In this respect, NFS transforms a workload consisting of a multitude of asynchronous write operations into a workload consisting of an even larger number of operations that are, by definition, synchronous.

What used to be a multitude of asynchronous file operations becomes an even larger multitude of synchronous writes once the commands arrive at the NFS server and finally on the disks. More or less a complete transformation of the workload.

So at the end the runtime of the tar -x is a product of the number of files in the tarball multiplied with processing time per file.

The processing time is the sum of

- the number of all RPC calls per file multiplied by the RPC round-trip time (RTT)

- the number of sync NFS operations per file multiplied by the persistence latency (excluding RTT). This is of course a first-order approximation. Some factors are excluded for brevity.

For a complete image you would have to include the processing time of other commands, which may be very small, because they are answered from caches inside the server.

I think the easiest approximation if you are RTT-bottlenecked or persistence-bottlenecked is to look at a packet trace. Compare the service times of a WRITE FILE_SYNC with an ACCESS or with a WRITE UNSTABLE. As I explain later, the very heuristics of writing longer files to NFS may deliver you some measurement points, as writing the file to the NFS server will usually use at least one command of each group.

The interesting measurement is the difference between the two (not the absolute value, as both kinds of commands can be objectively slow). If there is a large difference between those commands (with a longer run time on the commands mandated to persist on disk) you are persistence bottlenecked. Especially interesting would be a difference in the rough ballpark of rotational latency of hard disks.

In the customer’s case I’m describing, the persistence latency clearly dominated the workload and led to the prolonged runtime.

It’s not quite that bad

Now, however, it must also be said that there are a number of optimizations in NFS that mitigate the problem somewhat. For this, I created tar files in four different sizes: 1k, 32k, 33k, and 64k. The tcpdumps are reduced to CREATE, WRITE, and COMMIT calls.

I start with the 32k file. You can see that the writes are marked as UNSTABLE. Such a call is allowed to return without the data having been persisted to disk beforehand. However, at the end of this sequence there is a COMMIT command. This then persists the writes permanently to disk, and it only returns once the data has been safely written to a non-volatile storage medium.

25 0.000284 0.007877 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 234 V3 CREATE Call, DH: 0x24bc098f/32kfile Mode: GUARDED

53 0.000002 0.015328 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 846 V3 WRITE Call, FH: 0x58dd2c54 Offset: 0 Len: 32768 UNSTABLE

65 0.000366 0.018675 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 190 V3 COMMIT Call, FH: 0x58dd2c54

The situation looks a bit different with the 1k file:

79 0.000351 0.021063 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 234 V3 CREATE Call, DH: 0x24bc098f/1kfile Mode: GUARDED

83 0.000867 0.024100 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 1222 V3 WRITE Call, FH: 0xc5d2cd22 Offset: 0 Len: 1024 FILE_SYNC

This write is sent directly as FILE_SYNC. The reason is obvious when you look at what is missing: there is no final COMMIT. That saves a round trip, because the FILE_SYNC write already ensures that the data is persistent. It is unnecessary to enforce it again via a separate command.

Out of curiosity I also looked at the 33k and 64k sizes. First 33k:

101 0.000348 0.036633 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 234 V3 CREATE Call, DH: 0x24bc098f/33kfile Mode: GUARDED

131 0.000001 0.040300 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 846 V3 WRITE Call, FH: 0x38903d60 Offset: 0 Len: 32768 UNSTABLE

135 0.000160 0.040743 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 1222 V3 WRITE Call, FH: 0x38903d60 Offset: 32768 Len: 1024 FILE_SYNC

142 0.001003 0.046502 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 190 V3 COMMIT Call, FH: 0x38903d60

And now 64k:

156 0.000239 0.050702 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 234 V3 CREATE Call, DH: 0x24bc098f/64kfile Mode: GUARDED

187 0.000001 0.054108 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 846 V3 WRITE Call, FH: 0xa59fdc16 Offset: 0 Len: 32768 UNSTABLE

214 0.000001 0.055688 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 846 V3 WRITE Call, FH: 0xa59fdc16 Offset: 32768 Len: 32768 UNSTABLE

227 0.000389 0.066764 10.0.2.11 -> 10.0.2.10 NFS 190 V3 COMMIT Call, FH: 0xa59fdc16

I am not an expert on the NFS code, but my suspicion is that during development it was assumed that further write operations are to be expected when the WSIZE is utilized. If a bucket is filled to the brim, the probability is high that I will need at least one more only partially filled bucket. If you do not fill the WSIZE, it is likely that it is the last or the only write. The half-empty bucket is probably the last one.

So it is not that easy to say that NFS always writes synchronously. That was the case in NFSv2 and the cause of a number of NFS performance problems. NFSv3 introduced the concept of asynchronous NFS writes with a final synchronous COMMIT.

However, these optimizations are bypassed by a tarball with many small files. If you unpack a tarball with 290,000 files smaller than 32k (as an example in the customer’s configuration), you will see a large number of NFSv3 SYNC WRITES, hardly any asynchronous writes, and hardly any COMMITS.

If you unpack a tarball of the same total size with relatively few but large files, the data would be written much faster. It would mainly produce asynchronous writes, a few synchronous metadata operations, and the writes would be completed by a few synchronous COMMITS.

At the time, I was able to show the customer that the difference in the execution time of tar -x between a local filesystem and a remote filesystem via NFS was a direct and necessary consequence of how NFS works, made worse in its effects by the pool configuration chosen by the customer.

Solution to the problem

How do you improve this situation? This problem has existed for some time, and so there are a number of solutions for it.

Just to give you an idea of how long the problem has existed: perhaps some of you have been in the business long enough to know the Prestoserv NFS accelerators. They were really useful in NFSv2 days when every write truly was synchronous. The idea behind it was to provide very fast storage onto which the data was first persisted. In that case it was battery-backed RAM on the Prestoserv card (which is why you should really avoid pressing the reset button on the card). This allowed writes to a non-volatile medium to complete much faster, so the synchronous write could report completion before it hit the disk, but still fulfill the guarantee „If the call returns, it’s on non-volatile storage“. That said, the concept had a larger problem, especially in clusters, because only the disks and the Prestoserv card together represented the filesystem state guaranteed by synchronous write semantics. The card, however, was installed in one server and obviously did not migrate to the other server during a cluster failover.

The fundamental solution is still the same: reach the state on the NFS server such that a synchronous write can be returned as quickly as possible. And that usually boils down to taking mechanical disks out of the equation as much as possible. A technical implementation is, for example, the log devices in the ZFS Storage Appliance. From NFS’s point of view, a write is considered stable when the operating system returns from the synchronous write call. And the operating system (in this case Solaris with ZFS) can do this even with a large pool of magnetic disks by providing write-accelerating SSDs. The ultimately data-holding medium is still the hard disk, but ZFS returns the write call as soon as it has been persisted on the SSD. This function is called “separated ZFS Intent LOG”.

For this reason, in my work with the ZFS Storage Appliance, customers never get a system without write-accelerating SSDs unless they can prove to me that they have a workload that does not run into this problem—for example, if they can guarantee that nobody will ever run a tar and only large video streams are stored. Or if the customer explains that they have understood the problem but still want it that way. Because, as we say in Germany: „Kunde ist König“ … the customer is king.

Furthermore: if you tell me that you built your own NFS server, you should either have storage with non-volatile cache or also use log devices.

Without SSDs, for these workloads you essentially get the performance of a normal storage array when the cache battery is broken and the array switches to write-through.

You might think: “Naaah … tar -x isn’t that problematic. I do it rarely.” But you have no idea how often in my career I have seen workloads where tarballs are unpacked somewhere in a business-critical area: sensor data that gets unpacked, development file servers, diagnostic data from machines. This small useful tool tar is used in many places where you would not expect it.

Conclusions

What are my conclusions from the situation back then:

- Even simple things can become very complicated and problematic due to subtleties.

- Sometimes the simple workloads are the pathological workloads.

- It always helps to know the appropriate RFCs for a problem.

2026

I wrote this text in 2017 based on a problem that had appeared in my professional practice two years earlier. Since then, quite some time has passed. Technology has changed. However, the problem has not changed in many respects.

I’m seeing more and more NFSv4 implementations nowadays. However, unpacking a single file still leads to a significant number of RPC exchanges.

4 3.658097 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 286 V4 Call (Reply In 6) getattr GETATTR FH: 0x026e0906

5 3.658212 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 TCP 66 2049 → 1023 [ACK] Seq=1 Ack=222 Win=32806 Len=0 TSval=899272 TSecr=844284

6 3.658521 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 362 V4 Reply (Call In 4) getattr GETATTR

7 3.659236 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 294 V4 Call (Reply In 8) access ACCESS FH: 0x026e0906, [Check: RD LU MD XT DL]

8 3.659366 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 378 V4 Reply (Call In 7) access ACCESS, [Allowed: RD LU MD XT DL]

9 3.659744 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 358 V4 Call (Reply In 10) lookup valid LOOKUP DH: 0xcdc9c445/jmoekamp

10 3.659851 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 178 V4 Reply (Call In 9) lookup valid NVERIFY Status: NFS4ERR\_SAME

11 3.660285 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 294 V4 Call (Reply In 12) access ACCESS FH: 0xcdc9c445, [Check: RD LU MD XT DL]

12 3.660432 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 378 V4 Reply (Call In 11) access ACCESS, [Access Denied: MD XT DL], [Allowed: RD LU]

13 3.660945 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 286 V4 Call (Reply In 14) getattr GETATTR FH: 0x026e0906

14 3.661071 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 362 V4 Reply (Call In 13) getattr GETATTR

15 3.661773 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 286 V4 Call (Reply In 16) getattr GETATTR FH: 0x026e0906

16 3.661896 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 442 V4 Reply (Call In 15) getattr GETATTR

17 3.668453 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 414 V4 Call (Reply In 18) open OPEN DH: 0x026e0906/test1

18 3.670813 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 762 V4 Reply (Call In 17) open OPEN StateID: 0x3aa3

19 3.671881 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 326 V4 Call (Reply In 20) setattr SETATTR FH: 0x1d14c75e

20 3.673187 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 382 V4 Reply (Call In 19) setattr SETATTR

21 3.673623 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 274 V4 Call (Reply In 22) access ACCESS FH: 0x1d14c75e, [Check: RD MD XT XE]

22 3.673740 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 186 V4 Reply (Call In 21) access ACCESS, [Access Denied: XE], [Allowed: RD MD XT]

23 3.674939 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 1326 V4 Call (Reply In 24) write WRITE StateID: 0xf88c Offset: 0 Len: 1024

24 3.676379 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 194 V4 Reply (Call In 23) write WRITE

25 3.677073 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 354 V4 Call (Reply In 26) setattr SETATTR FH: 0x1d14c75e

26 3.678309 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 382 V4 Reply (Call In 25) setattr SETATTR

27 3.678828 192.168.3.242 192.168.3.100 NFS 310 V4 Call (Reply In 28) close CLOSE StateID: 0x3aa3

28 3.678957 192.168.3.100 192.168.3.242 NFS 386 V4 Reply (Call In 27) close CLOSE

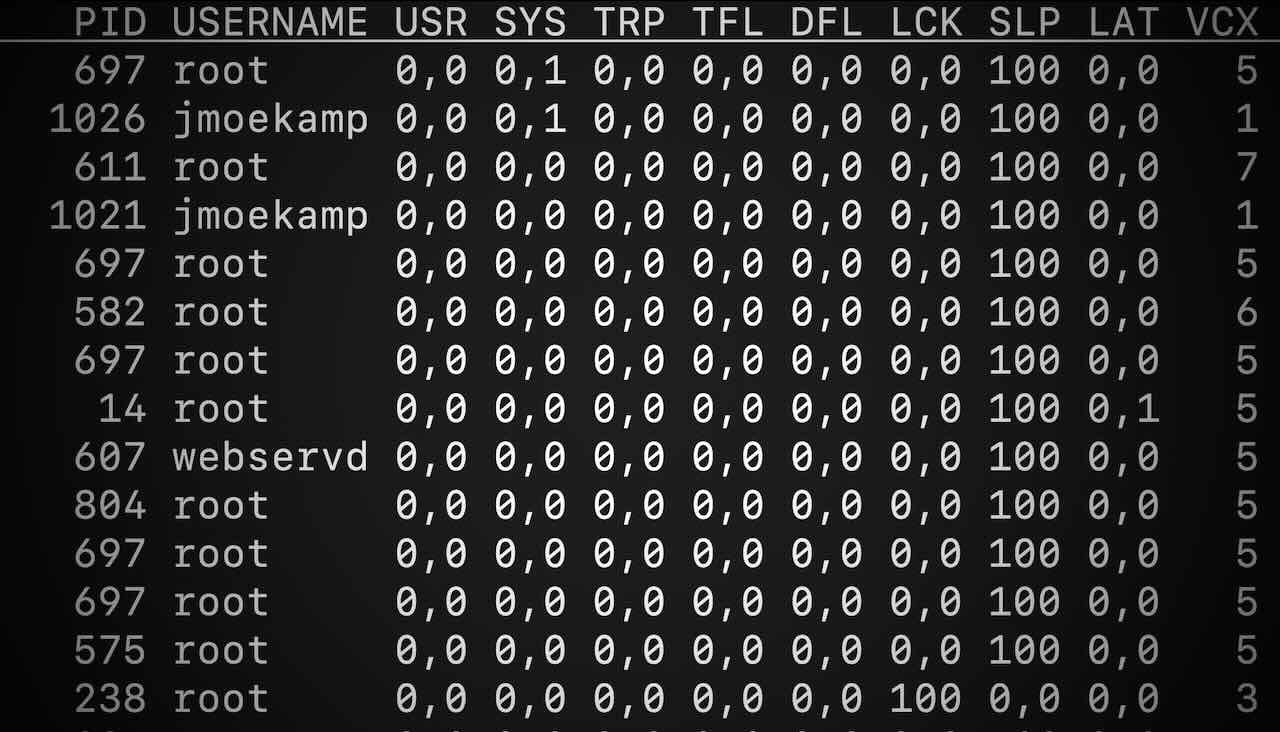

I did some additional statistics on a tar -x with 5 files:

| Index | Procedure | Calls | Min SRT (s) | Max SRT (s) | Avg SRT (s) | Sum SRT (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACCESS | 3 | 7 | 0.000104 | 0.000147 | 0.000116 | 0.000815 |

| CLOSE | 4 | 5 | 0.000111 | 0.000129 | 0.000120 | 0.000598 |

| GETATTR | 9 | 7 | 0.000109 | 0.000424 | 0.000162 | 0.001132 |

| NVERIFY | 17 | 1 | 0.000107 | 0.000107 | 0.000107 | 0.000107 |

| OPEN | 18 | 5 | 0.000878 | 0.003477 | 0.002041 | 0.010205 |

| SETATTR | 34 | 10 | 0.000818 | 0.005882 | 0.002415 | 0.024154 |

| WRITE | 38 | 5 | 0.000903 | 0.009665 | 0.002828 | 0.014139 |

As you see, the most time is used in the NFS calls with synchronous write semantics.

This is related to the fact that the requirements for NFSv4 are essentially unchanged. RFC 7530 states in section 14.3:

NFSv4 operations that modify the file system are synchronous. When

an operation is successfully completed at the server, the client can

trust that any data associated with the request is now in stable

storage (the one exception is in the case of the file data in a WRITE

operation with the UNSTABLE4 option specified).

The newer RFC 8881 specifying NFSv4.1 doesn’t change this behavior.

If you want to preserve all the consistency guarantees that NFS offers, then there is no way to bypass this requirement of synchronous writing.

If you look at the packet capture of an NFSv4 communication, you find fairly similar communication for WRITE, only here it is packaged into compound operations. Here too the client requests synchronous write semantics by requiring FILE_SYNC4 when stable.

Network File System, Ops(3): SEQUENCE, PUTFH, WRITE

[Program Version: 4]

[V4 Procedure: COMPOUND (1)]

Tag: write

minorversion: 1

Operations (count: 3): SEQUENCE, PUTFH, WRITE

Opcode: SEQUENCE (53)

Opcode: PUTFH (22)

Opcode: WRITE (38)

StateID

offset: 0

stable: FILE_SYNC4 (2)

Write length: 1024

Data: <DATA>

length: 1024

contents: <DATA>

[Main Opcode: WRITE (38)]

FILE_SYNC4 is defined as follows:

If stable is FILE_SYNC4, the server must commit the data written plus all file

system metadata to stable storage before returning results.

That said, progress in storage technology alleviates the problem from a different vector: If the storage itself has very low write latencies (like solid state disk), the situation is still the same, however the impact of those synchronous write operations is much smaller. However, depending on the size of your storage and your budget constraints this may not be an option. And that’s the point where using write-accelerating SSDs in ZFS gives you the opportunity to provide large storage spaces on hard disks and still solve the latency problem where it matters most.

Different solutions

Of course there are other options to accelerate things. However, they either work by parallelizing the job (e.g. multiple tarballs), weaken the durability contract, or take NFS out of the equation.

Parallelization doesn’t change the behavior of NFS, however it breaks the rigid sequentiality by having multiple streams of rigid sequentiality.

For example you could set the sync=disabled property of ZFS. This accelerates the workload, but in case of a server crash you can lose the last 5–10 seconds of writes (depending on the ZFS transaction group window). NFS hasn’t changed — the server is effectively acknowledging “stable” operations before the data is actually on non-volatile storage.

Another solution could be unpacking the tarball on a system with local access to the target filesystem. The unpacking is then local and thus very fast. Since tar typically does not enforce synchronous writes, you get a largely buffered/asynchronous write stream. This is an option if you have shell access; it is often not feasible on storage appliances. And keep in mind: this works precisely because you are circumventing NFS altogether.

Be the first to reply! ↗